- April 1, 2025

Hawaii’s Production Community Rallies for Industry Survival as Jobs Disappear

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

Threads

Email

Latest Blogs

Related News

- June 23, 2025

Netflix has secured a $20 million tax credit from the state of California for an untitled feature film, topping the latest round of allocations from the state’s competitive film and television tax inc...

- June 23, 2025

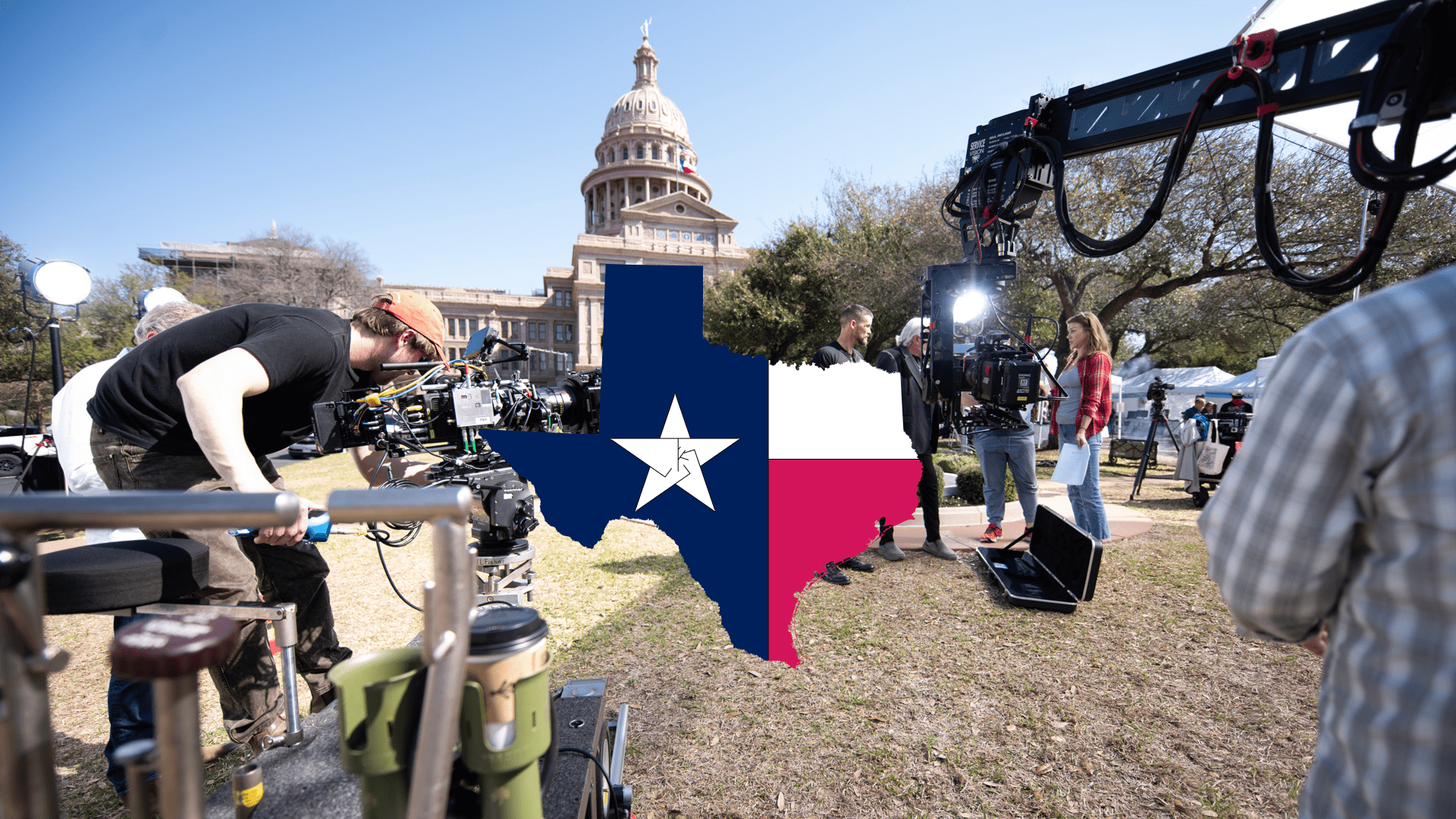

Texas has made its boldest move yet to reclaim its cinematic legacy—doubling down on its production incentive program with a historic funding boost aimed at luring back filmmakers and deterring the gr...

- June 22, 2025

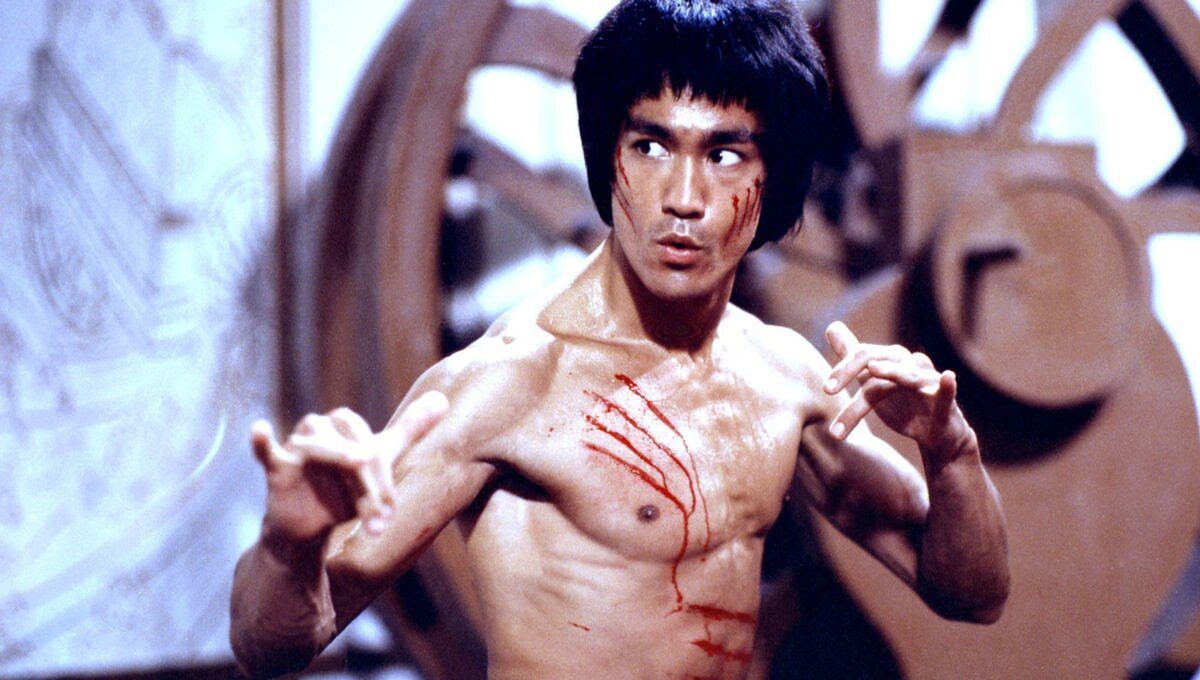

At the 27th Shanghai International Film Festival, industry heavyweights unveiled a sweeping—and government-backed—initiative to breathe new life into martial arts cinema using artificial intelligence....

- June 22, 2025

Apple TV+ is doubling down on prestige cinema, inking a multi-year, first-look deal with Chernin Entertainment—the powerhouse production banner behind Ford v Ferrari, The Planet of the Apes franchise,...

- June 21, 2025

The internet is buzzing this week with a striking new wave of AI-generated franchise vlogs, and the most explosive among them is “A Stormtrooper Vlog | The Adventures of Dave and Greg”. This immersive...

- June 19, 2025

A bold new chapter in Northern Ireland’s production landscape begins this week with the official opening of Studio Ulster—a state-of-the-art virtual production facility designed to compete on a global...

- June 18, 2025

As lawmakers weigh a $750 million expansion to California’s tax credit program, insiders argue the clock is running out on the state’s production future. On June 11, a cross-section of Hollywood creat...

- June 18, 2025

The longest-operating film studio in Los Angeles is now for sale—offering not just a rare slice of industry real estate, but a stark test of the current demand for production space in Hollywood’s post...

- June 17, 2025

In response to a dramatic slowdown in scripted television production across Los Angeles, major soundstage owner Hackman Capital Partners is taking a bold new direction — opening facilities to social m...

- June 16, 2025

In a significant move that further cements Georgia’s status as a film and television production powerhouse, the Georgia Film Academy (GFA) has announced a new partnership with Assembly Studios that wi...