When Mountainhead premieres tonight on HBO and Max, it won’t just mark Jesse Armstrong’s return to HBO or his first feature film. It will stand as a blistering case study in rapid-fire production—conceived, shot, and edited in a time frame more common in software sprints than scripted drama.

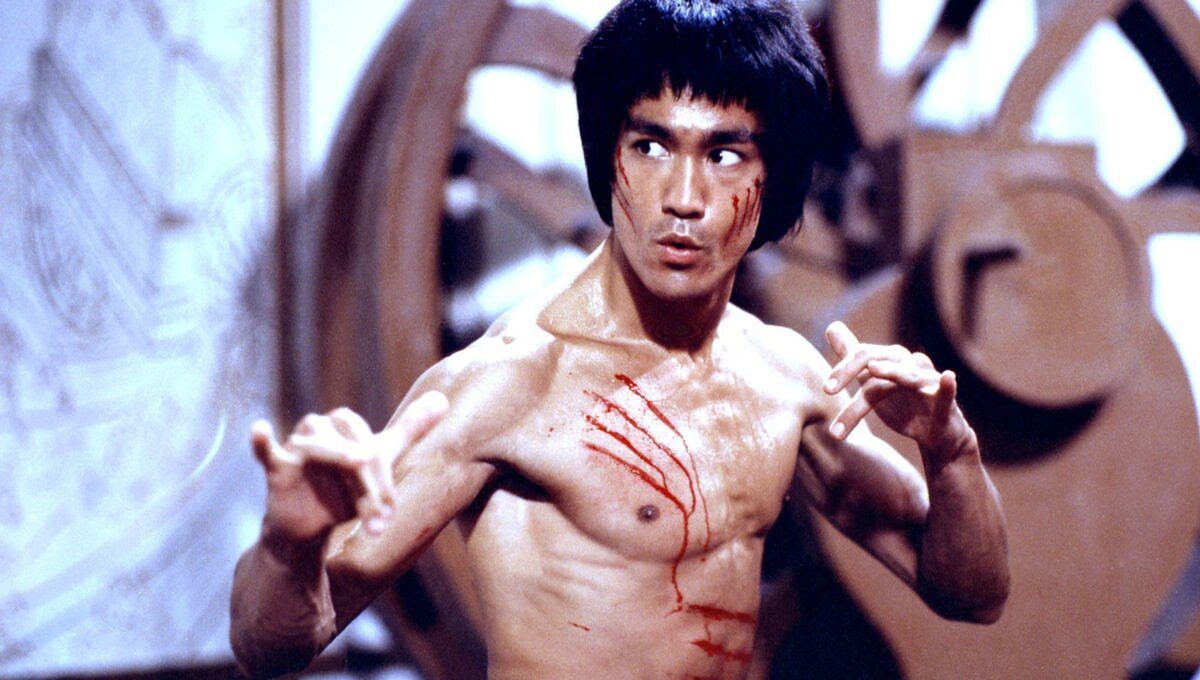

The biting satire, starring Steve Carell, Jason Schwartzman, Ramy Youssef, and Cory Michael Smith, follows four billionaire founders gathered for a “no staff, just bros” weekend in a mountaintop mansion. But as the world below descends into chaos—thanks to an AI tool one of them helped unleash—the film’s central question becomes: Do these gods on the hill intervene, or do they cash in?

The answer is complicated, and Mountainhead’s production was no less so.

Speed as a Strategy

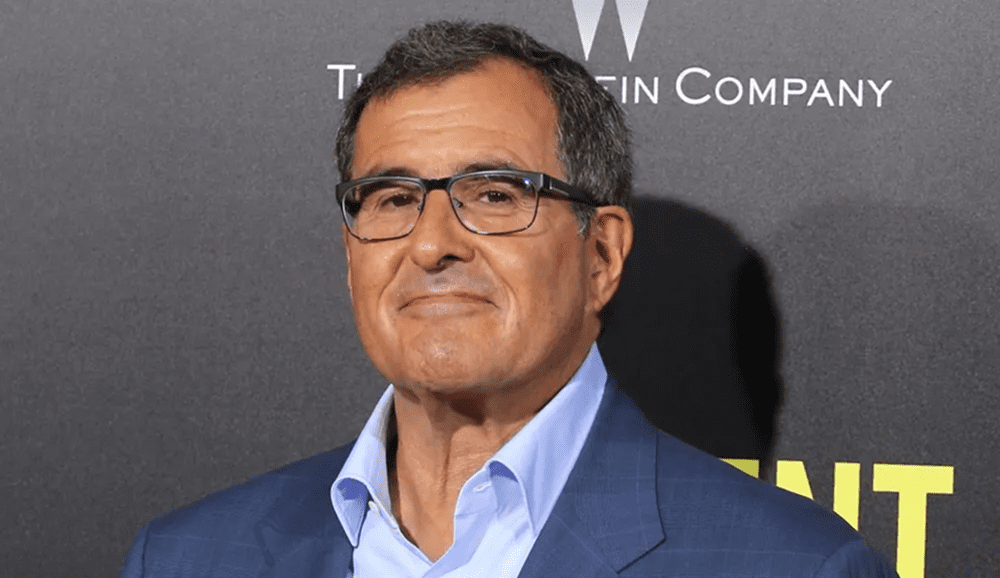

The idea for Mountainhead came fast—and so did everything else. After writing a review of Going Infinite, the Michael Lewis book about Sam Bankman-Fried, Armstrong dove deep into the world of crypto evangelists, AI podcasts, and the distinct cadence of tech bro speech. By December 2024, he had pitched HBO’s Casey Bloys. By January, Steve Carell was in. Filming began in March and wrapped in April. The film locked just in time for its May 31 Emmy eligibility window.

“The bubble of nowness floats pretty fast,” Armstrong said. “We had to move at the speed of the people we were satirizing.”

Armstrong rebuilt his Succession core team like a startup hiring its founding engineers: EP Frank Rich, writers Lucy Prebble, Tony Roche, and Will Tracy, costume designer Susan Lyall, production designer Stephen Carter, cinematographer Marcel Zyskind, and editor Bill Henry. With the DNA of Succession baked in, the team operated like a crew fluent in crisis-mode creativity.

Finding the House at the Top of the World

At the heart of the production—and the story—was the mansion itself: Hugo Van Yalk’s Mountainhead. But there was no time to build one. With the shoot just weeks away, the team scouted real-world megamansions from Whistler to Jackson Hole before landing in the snowy peaks above Park City, Utah.

Stephen Carter, who previously worked with Armstrong on Succession, described the process as an architectural treasure hunt. “We needed a house that could keep us visually excited for two hours of screen time,” he said. “Some were beautiful but lacked variety. Others looked promising online, but had new construction right next door or no cinematic depth.”

Ultimately, the team found what they dubbed “Rockstar House”—a sprawling, bizarrely luxurious fortress perched 8,000 feet up. Complete with a bowling alley, basketball court, bar, climbing wall, and glass-wrapped rooms with panoramic views, the home became a character of its own.

“I can’t imagine it being another house,” Carell said. “Scene choices changed because of this house. We were consumed by its vibe.”

But not everyone was enamored. “That house made me feel physically sick,” Zyskind confessed. “It’s like a violation on the mountain.” Armstrong agreed: “That was the gut feeling we were looking for.”

The Anti-Hollywood Workflow

In traditional production, you prep for months, shoot for weeks, then edit for as long as your budget allows. Mountainhead did it all in half the time.

Armstrong wrote the core script in ten days—some of it in the back of a van during location scouting. There was no luxury of table reads or slow rewrites. The actors signed on before the script was even finished.

Filming ran like a Succession episode on steroids: long scenes, minimal takes, handheld cameras that roamed freely as the actors played entire scenes in real time. They shot 10-hour days with rolling lunches—no stopping to reset the light or rethink a shot. “There was no time to second-guess,” Carell said. “Everything was instinctual.”

Post-production was equally compressed. Editor Bill Henry cut scenes from London while footage was uploaded nightly from Utah. By Saturday, Armstrong and the team would review the previous week’s scenes together over Zoom. They started with a 165-minute cut. They locked at 109. Fast.

“It stops you from overworking the cut,” Henry said. “You’re not tinkering—you’re making decisions.”

A Satire That’s Alarmingly Timely

Set during a weekend that turns into a global reckoning, Mountainhead is a film about AI disinformation, unchecked billionaire power, and the moral ambiguity of modern tech leadership. In other words: it’s happening now.

“There’s a spectrum between confidence and arrogance,” Armstrong said. “These men believe they’re the solution. And that belief shapes our world.”

Much like its characters, Mountainhead was built quickly, decisively, and without apology. Armstrong didn’t wait for the world to change again before making his film about the now. He knew the window wouldn’t stay open long.

The New Model? Maybe.

Production designer Stephen Carter joked, “If we succeed doing it this fast, they’ll try to make us do it again.” But everyone involved—from the cast to the crew—seems game for round two.

“It was lightning in a bottle,” said executive producer Jill Footlick. “Sure, we’d take more time if we had it. But I’d do it again in a heartbeat.”

Armstrong may have aimed to satirize tech’s god complex—but in process, he mimicked its speed, agility, and audacity. Mountainhead doesn’t just lampoon a world ruled by algorithms and ambition. It was made in its image.