Excitement about Netflix and Amazon’s investment has evaporated as strikes, falling ad spend and a glut of completed shows leaves crews out of work.

Earlier this year things appeared to be looking up for the UK’s £6bn TV and film production industry, with US streaming firms revealing billions had been spent on shows and films made in Britain.

An announcement from Amazon that it had doubled its investment in the UK, where it now makes dramas including the Lord of the Rings prequel, The Rings of Power, followed news from Netflix that it was spending about $1.5bn (£1.2bn) annually on British-made movies and series such as The Crown and Heartstopper.

But now the sector faces compound crises, including shutdowns on the back of Hollywood strikes and a plunge in commissions from homegrown broadcasters who are sitting on a glut of programmes completed after the pandemic while struggling with budgets depleted by falling advertiser spending.

The union Bectu estimates three-quarters of freelance film and TV crew in Britain are now out of work, prompting observers to question whether the UK broadcasting industry is facing a temporary post-pandemic reset or an existential crisis.

“I have never known so many people in the TV and film industry out of work in this country,” says the boss of one big UK production company. “I think this is the year when everything changes.”

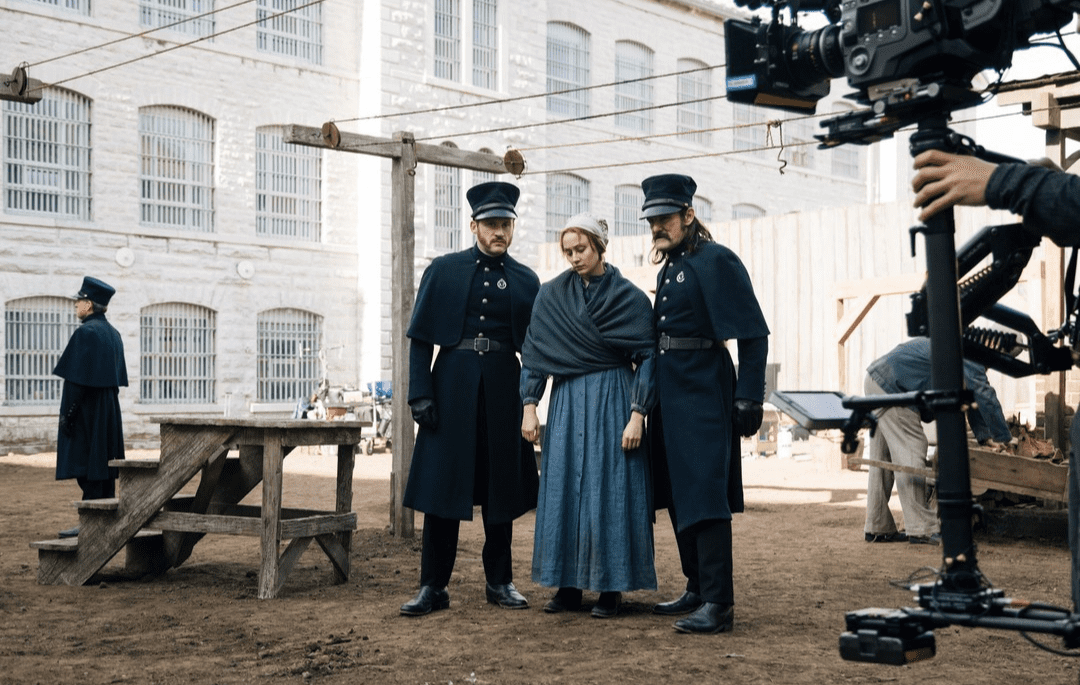

On the face of it the headline-grabbing issue of the first strike by Hollywood writers and actors in 60 years – which has seen work halt in the UK on movies such as Deadpool 3 and Wicked and also on expensive TV shows such as Apple TV+ production Silo – is a financially crippling blip that will eventually be resolved.

The picket lines may be across the Atlantic but the UK remains the second-biggest global market for film and high-end prestige TV productions, with 86% of the £6.27bn spent on productions last year coming from mostly Hollywood studios and streamers, according to the British Film Institute.

“The US strikes have had an immediate and catastrophic effect on the film and TV industry in the UK,” says one worker, a set decorator working at a major UK studio on a Hollywood project who was dismissed overnight as the strikes began. “All the major studios are like ghost towns now. I’ve not seen anything like it since Covid.”

While times are tough not everyone is sympathetic, with one TV and film industry executive saying that the boom in content after pandemic restrictions eased was very lucrative for freelancers working on big-budget projects.

“There was so much work you couldn’t get crew so labour rates went through the roof,” says one executive. “Various grades of workers were getting paid from 30% to double their previous rate; they did extremely well because that is how the market works. Strikes aside, there was always a market correction coming anyway. But it’s not the end of the world.”

That correction is filtering through to the previously hectic rush for studio space that had seen largescale projects pop up at breakneck speed, and big players such as Netflix, Disney and Amazon scramble to secure long term deals to secure the pipeline of productions.

The recently -opened £150m Shinfield Studios next to the M4 in Reading, which will be the UK’s fourth-largest production space when it is completed, is understood to have secured Disney in a multi-year, multi-production deal. However, it is understood that after Disney finished filming Star Wars series The Acolyte the company exercised a clause to pull back on the deal as market conditions deteriorated.

Disney and peers across the industry including Netflix and Warner Bros Discovery have moved to significantly cut back on profligate spending as investors demanded their heavily loss-making streaming services become profitable.

“Look, it is a bit of a storm at the moment but it’s not the end of the golden age of TV,” says John McVay, chief executive at Pact, the body that represents the hundreds of independent UK production companies. “The UK TV industry is very resilient and adaptable. It may be the case that it becomes a bit different going forward, there may not be such massive spending. It may be the case that [commissioners] don’t necessarily spend less, but spend more wisely.”

In the UK the recalibration of spending has become even more acute as broadcasters that rely heavily on the ad market, such as Channel 4, ITV, Channel 5 and to an extent Sky, cope with an unexpected slump in spending from advertisers.

Months after Channel 4 paid its top executives millions for its performance last year, including the highest annual pay for a chief executive in its 40-year history, the broadcaster cancelled shows and introduced a commissioning freeze.

While it intends to lift the months-long suspension in the coming weeks, the move was at least in part a response to a double-digit percentage fall in TV ad spend, on linear and digital TV channels as well as streaming services.

The UK TV ad market is on track for its biggest annual decline since 2009, barring Covid-hit 2020, and is forecast to contract by almost 7%. While again there is a backdrop of a post-Covid boom correction – both Channel 4 and ITV enjoyed the best ad hauls in their respective histories in 2021 – there is also a sense that the decline may represent a deeper dissatisfaction with the traditional TV model.

While traditional broadcasters are scrabbling to reinvent themselves in the digital space – ITV is spending £800m-plus to get its ITVX streaming service fit for the Netflix era – the attraction of digital media alternatives such as TikTok, Facebook, Instagram and Google continues to grow.

“Unfortunately for sellers of TV advertising as ad-supported TV viewing falls and reach is harder to achieve, other media looks more appealing by comparison,” says Brian Wieser, principal of tech and media consultancy Madison and Wall.

“This is exacerbated as marketers evolve their goals to do things that digital may satisfy better. It’s not that TV won’t still be important, but it’s not positioned for growth.”

However, there are also those that believe the storm battering the UK production industry will blow over, saying there is always a demand for top quality content.

“Do I believe we are falling off a cliff? No, it is an unfortunate confluence of circumstances,” says Adrian Wootton, chief executive of Film London and the British Film Commission. “Look at content such as Barbie, Oppenheimer and Succession: no one is getting bored.

“There has been talk of a ‘reset’ of volumes and maybe 2024 won’t hit the peaks we have seen in the last few years. But the desire and the appetite among audiences is still there and we make more content than pretty much anywhere in the world outside North America.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I was hoping you would consider taking the step of supporting the Guardian’s journalism.

From Elon Musk to Rupert Murdoch, a small number of billionaire owners have a powerful hold on so much of the information that reaches the public about what’s happening in the world. The Guardian is different. We have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. Our journalism is produced to serve the public interest – not profit motives.

And we avoid the trap that befalls much US media – the tendency, born of a desire to please all sides, to engage in false equivalence in the name of neutrality. While fairness guides everything we do, we know there is a right and a wrong position in the fight against racism and for reproductive justice. When we report on issues like the climate crisis, we’re not afraid to name who is responsible. And as a global news organization, we’re able to provide a fresh, outsider perspective on US politics – one so often missing from the insular American media bubble.

Around the world, readers can access the Guardian’s paywall-free journalism because of our unique reader-supported model. That’s because of people like you. Our readers keep us independent, beholden to no outside influence and accessible to everyone – whether they can afford to pay for news, or not.

Article originated: The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2023/sep/15/britain-tv-and-film-industry-decline